The State of Dairy Markets

Katelyn Walley, Business Management Specialist and Team Leader

Southwest New York Dairy, Livestock and Field Crops Program

A message from Katelyn Walley-Stoll, Farm Business Management Specialist with Cornell University Cooperative Extension's Southwest New York Dairy, Livestock, and Field Crops Program:

A lot of people have been asking me about all of the photos and videos going around of milk being dumped. This is a long, but explanatory article from two industry experts, with some tips and things for farms to think about in these uncertain times. At the end of the day, remember that our food supply is safe, you will still be able to buy milk, and farmers keep farming. Keep our farmer's in your thoughts and buy a couple extra blocks of American Made cheese or tubs of ice cream. Don't forget, I put together a monthly report called Dairy Market Watch that is an educational newsletter to keep producers informed of changing market factors affecting the dairy industry. To subscribe, click here and enter your contact information. Stay safe - Katelyn.

A Note from Andrew Novakovic, The E.V. Baker Professor of Agricultural Economics Emeritus, Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management, Cornell University.

Our old friend Mark Stephenson took the time to write down some thoughts about dairy markets. Consider it a letter to Wisconsin farmers. There are a few little bits that were written with specific Wisconsin stuff in mind, but all of it is pertinent to us. Indeed Mark has done his usual excellent job.

Dumping, at least on a wider scale, is a new thing for Wisconsin. We are starting to hear about it here, although my gut tells me it will be less of a problem for us than Wisconsin when everything is said and done. We have vulnerabilities, but our customer base is 1) more diversified, 2) less export dependent, and 3) more oriented to retail sales. Wisconsin is 90% cheese and a lot of that cheese is 1) specialty varieties that are not conducive to storage and 2) headed to restaurants. Other states will be harder hit by export disruptions, primarily the West.

Our marketing profile may give us an edge on having a customer for our products, but it remains the case that our prices float on top of Class III and IV markets. Those markets are taking a big hit because they are the ones most deeply impacted by disrupted foodservice and export markets. Class I sales will remain up, by 10% or more, as long as we are eating at home. Class II appears to be a bit more of a mixed bag. Some stuff is doing well with more at home consumption (yogurt in particular), other products not so much (lots of cream goes to coffee shops).

Farms who are members of larger cooperatives will be relying on their cooperatives to sort out sales channels. Farms belonging to small cooperatives or who direct ship to a plant will quickly find out if their customer is enjoying higher sales or the other way around. It is the latter that will most likely result in some farms or some loads not being able to find a home.

I don't know if Congress will agree to re-open DMC or just how generous USDA will be with the new money they got for the CCC, which (as Mark notes below) can be used for direct subsidies to farmers or to shore up demand by purchasing dairy products. I am skeptical about DMC but I have learned that anything is possible, especially in an election year. I will also share with you that I think we have to be a little careful in what we ask for. Direct subsidies to farmers can be a big adrenaline injection to the farm business and no one among us would say dairy farms don't need some help, but this approach has the effect of stabilizing supply while doing nothing to improve demand. We already have a problem with prices declining because of net declines in total demand. If we protect supply but do nothing to improve demand, we will only see market prices stay stuck in low gear and maybe go even lower in order to clear markets. Especially if we implement new programs to protect supply (farmers), we may well be in a market situation where prices will be in the doldrums for a couple of years. We have to get out of the current public health scenario first, which is going to take a while, and then we will find that we and a bunch of other major milk producing countries have large stocks of powders and cheese that have to get worked off before we will see any improvement in price.

Every farm needs to think long and hard about how they get through the next few years. I caution against over-reacting in either direction but then that begs knowing what the Goldilocks reaction is. I might suggest starting with the question, can you survive another 3 years that look a lot like the last 4 years? Or, what do you need to do in order to make it through that gauntlet. Energy will likely remain cheap and that would be a good bet for corn and soybeans at this time. Interest rates will likely stay very low. That will help.

Andy

State of Dairy Markets as of April 1, 2020.

By Mark Stephenson, Director of Dairy Policy Analysis, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

It's a little ironic that today is April Fools day. Our circumstances are no joke, and I feel a need to share what we know about deteriorating dairy markets. Nobody needs a review as to how difficult the last 4-5 years have been for dairy producers, but the 4th quarter of 2019 began to show us that 2020 would be a recovery year. And, in speaking with a handful of lenders, I was told that most farms had managed to pay down their open accounts, perhaps pay some principal on loans that had been interest only, and restore some of their working capital. In short, many borrowers had moved up a point or two on their credit worthiness score. This alone put many folks in a better position to encounter our current crisis. We are writing the play book daily as the COVID plight unfolds, but all of the lenders I spoke with indicated that they are not panicking and most of their borrowers will be supported over the next several months. However, there are some farms who did not improve their position and to whom credit has been fully extended.

Futures markets continue to deteriorate.

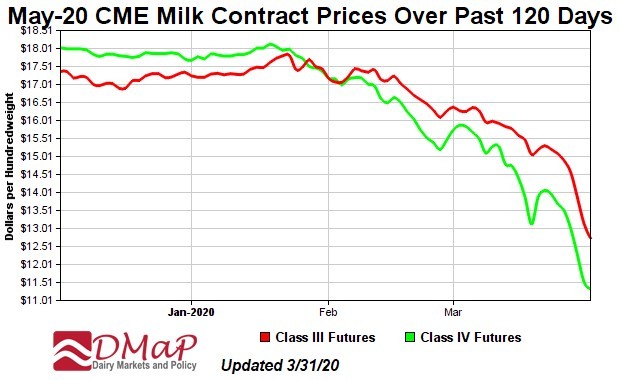

The first news of coronavirus hit the United States in mid-to-late January. This was not the virus in the U.S., it was news about the outbreak in China. The markets reacted negatively to that news because China has been the world's largest importer of dairy products. Clearly, if that country was going to be battling an epidemic, they would not be importing as much product and that had implications for our dairy export markets. Futures prices dropped about 70¢ in a single day based on the first news. As COVID-19 spread to other countries including the U.S., markets continued their pessimistic tone (see graph of May milk futures prices below).

By last week when states began to issue shelter at home edicts, our domestic dairy markets took a sharp turn. As customers stopped eating at food service establishments and stocking their pantries for home consumption, product demands changed overnight. American processed cheese—the singles slices that may be individually wrapped and put on a fast food hamburger, or the semi-plastic cheese that gets served over a plate of nachos—stopped being ordered by restaurants. Barrel cheese plants that make the precursor cheese for processed products, experienced a sharp decline in orders. But the good news was that beverage milk and other dairy products were flying off the shelf in retail stores. Fluid milk sales, which have been in decline for many years, experienced a surge in demand.

Milk gets dumped.

In all of this turmoil, the dairy supply chain has managed to be resilient. Behind the scenes, milk has shifted from away from some plants and to those who were scrambling to keep up with retail orders. But, a few organizations sent letters out to their producers alerting them that we could see some disruptions and that milk may need to be dumped. There have been other communications asking farms to consider reducing milk production to help balance market needs. Rumors began to circulate that milk was being dumped without any credible knowledge of an actual farm who dumped their milk… until yesterday.

We do know of a handful of farms that were asked to dispose of the day's milking. This occurred in a few locations across the state and primarily from one cooperative. I don't know the circumstances which initiated the need—it could be a single plant that closed either temporarily or permanently, it could be a decline in orders for finished product which got pushed back due to less milk needed. The bottom line though is that there wasn't enough demand immediately available to take this milk even at distressed prices.

This seems to be an orderly request to dump milk. It is a few larger farms that have been asked and not dozens of smaller farms. It seems to be farms with lagoon capacity to handle the milk and not require immediate land spreading. It also seems to be distributed across the state and not all from one region.

We haven't experienced much milk dumping in the Upper Midwest in recent years, but the Northeast and Michigan have had periodic dumping. In those cases, the lost value for the milk was reblended across the cooperative's membership so that the few who did dispose of their milk did not have to bear the full burden of the loss. I expect that the cooperatives in our state who need to dump milk will reblend the losses across their members as well. It could be much more difficult if direct shippers are dropped by the plant they ship milk to.

Short of dumping, farms could also find that milk can be sold at distressed prices. Direct shippers, smaller cooperatives or even larger ones may find that a plant simply doesn't need the milk and a new home must be found. If there is simply more milk than the market needs at this time, you could find a buyer who will be willing to pay you something for the milk but it may be significantly less than Federal Order minimum prices. This is called distressed milk sales. I have also heard that one smaller cooperative found a temporary home for member milk at very well below market prices—not quite dumped milk, but well less than cost of production.

How bad will it get?

You've all heard the maxim that markets hate uncertainty. If a pandemic (first in my lifetime) isn't uncertainty, I don't know what is. I suspect that the markets will continue to be heavily pessimistic about milk prices for the next several weeks. But, it is important to remember that futures markets are not spot markets where real product actually gets sold. And spot markets are not the same as wholesale markets which report actual, regular sale prices to USDA and which are used to calculate the minimum class prices in Federal Milk Marketing Orders. And, Federal Order minimum prices are not the same as what farms actually receive in their milk checks (they typically sell higher component milk than standard test and premiums are commonly paid above the Federal Order minimum).

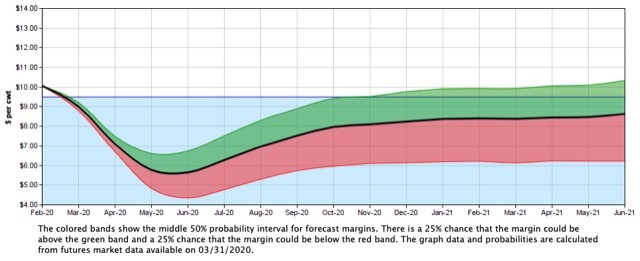

In looking at the Class III and IV futures prices right now (example graph above), I would forecast that to be something like a $14 farm price bottom in May-June time period (graph below). In 2009, those farm prices bottomed out in the mid $11 range, so this forecast isn't as low as that, but it would be worse than the lowest prices we've seen in the last 5 years. Low gasoline prices and ethanol prices are also keeping a lid on corn prices so there may be some relief for purchased feeds, although dairy quality alfalfa is expensive and difficult to come by.

A few months ago in early December, we were finishing the enrollment period for the 2020 Dairy Margin Coverage (DMC) program. At that time, forecasts were more optimistic and we were not expecting any payments for the program. Consequently, less than half of producers enrolled in the program and many producers elected to stay at the catastrophic level of $4.00 protection. Today, our forecasts show DMC payments beginning with next month's milk at the $9.50 level of coverage and continuing through the rest of the year. In fact, the May and June margins are forecast to be below $6.00 (graph below)

Is there relief?

Producers who enrolled in the DMC and who signed up at the $9.50 level would receive as much a $3.50 payment on covered milk production for May and June and I would currently forecast an average payment of about $1.85 for the year. There has been some discussion about reopening the DMC enrollment to provide producers with another chance to enroll for the year. That didn't happen with the massive relief bill (CARES) just passed by Congress and signed by the President, but there is talk about another relief bill which might include a DMC do-over for producers.

The CARES act did include some significant funding for agriculture. There isn't much specificity yet about how much of the funding will make its way to the dairy industry or how it will be accessed, but there was $9.5B for the USDA Office of the Secretary, $14B for Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) replenishment, and an additional $15.8B for SNAP (food and nutrition). I'm guessing here, but the $9.5B may be used for direct payments to agriculture kind of like we received from the Market Facilitation Payments. The CCC funding is usually used for activities meant to lift market prices—imagine food purchases and give aways to food pantries, perhaps hospitals and the like. And the SNAP funds will be needed to provide newly out-of-work individuals with the ability to purchase food. All of these programs could help the dairy industry, but some of them will take weeks if not months to have an impact.

What can we do?

There isn't any playbook for our current crisis. The best pandemic modelers would forecast that we have months of social distancing ahead of us. And I think that it is also prudent recognize that the world's economy will take many months after that to pick itself up off of the floor. It will take time to gather the data, but our current unemployment will blitz the level of 10% that was the peak during the last recession. Our GDP growth is surely negative right now compared to the same month last year, so by the time we have two quarters of those results, we can officially declare ourselves in recession. That will take us many months more before we are back to healthy employment and economic growth.

I do think that our immediate milk dumping reflects several factors specific to the moment. For one thing, consumers certainly aren't going out to restaurants, so food service sales are almost non-existent (except pizza and a small amount of pickup or delivery sales). Retail sales surged while panicked consumers filled their pantries, but now we are eating out of our caches and don't need to visit the grocery store in the near future. But soon, we will all run down on those items and have to go out to replenish our supplies. I think that retail sales of dairy products will pick back up and find a new normal in the weeks ahead.

I also don't want to sugar coat such prognostications. I doubt that dairy product sales will be as large with our at-home eating as they were when much of our consumption was served through the food service sector. I also expect that export sales to other countries will begin to be restored, but that is some way off. The bottom line is that we have too much milk production for our times and we have plenty of dairy product in stocks. Dairy processors will not continue to purchase all of the milk to make product that they cannot sell. We either need to reduce the milk supply or find new demand or some combination of the two.

If our livestock sales outlets don't shut down, cull some cows. Either we do this by creating a bit of unused capacity in most of our barns (that's what happened in 2009), or we do this by survival of the fittest and we continue to take a heavy toll across our rural communities. These aren't normal times and much of the outcome is out of our personal control. Each of us will need to partition our worries into categories that we do control: feed, milk and care for animals; empty the lagoon and get ready for Spring planting; call your lender and let them know if your borrowing needs have changed; practice social distancing, good hygiene, and care for your workers and family. Convince yourself to set aside the things that are out of your control: the spread of, and cure for coronavirus; market prices; weather. For many of the items out of our control, there is a silent army of folks trying to fix the problem: doctors and researchers across the globe are working long hours on a cure and a vaccine; dairy plants and coops are looking for places to put your milk; industry trade organizations, departments of agricultural, universities and our elected officials are sifting through ideas to mitigate the problems. Finally, I would suggest that we take time to be thankful: most of us are warm at night, well fed and healthy; and we have our family and a greater circle of people who care about us.

It's going to be a rough year, but we'll get through to the other side. If you are feeling too despondent, call someone. All of us need emotional support and a virtual hug sometimes.

Mark Stephenson

--------------------------------

Mark Stephenson, PhD

Director of Dairy Policy Analysis

University of Wisconsin, Madison

427 Lorch St 202 Taylor Hall

Madison, WI 53706

Ph: (608) 890-3755

Upcoming Events

Cornell Organic Field Crops & Dairy Conference

March 6, 2026

Waterloo, NY

Farmers, researchers, educators, and agricultural service providers from across the Northeast are invited to the 2026 Cornell Organic Field Crops & Dairy Conference, held Friday, March 6, 2026, from 8:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. at the Lux Hotel & Conference Center in Waterloo, N.Y.

Co-hosted by New York Soil Health and Cornell CALS, the annual conference brings together leaders in organic grain, dairy, and livestock systems to share practical tools, new research, and farmer-tested strategies to support resilient and profitable organic production.

NY Pork Producers - 2026 Producer Summit & Annual Meeting

March 13 - March 14, 2026

Hamilton, NY

Join NYPP for the 2026 Producer Summit, where producers of all sizes and production styles will explore marketing, branding, selling pork, and current consumer trends through practical sessions designed to help build demand, connect with customers, and add value to their operations.

Mid Atlantic Grain Conference

March 15 - March 16, 2026

We're excited to share that the 2026 Mid‐Atlantic Grain Fair & Grain Conference is coming March 15-16, 2026 in Pennsylvania! This two-day event brings together farmers, millers, bakers, brewers, distillers, researchers, and grain enthusiasts to learn, connect, and celebrate local grains. These events will be offered at two seperate locations.

Announcements

No announcements at this time.